Galileo's Moon

Season 18 Episode 1 | 55m 3sVideo has Closed Captions

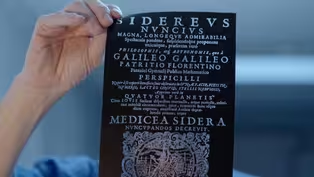

Join experts as they examine an alleged proof copy of Galileo’s “Sidereus Nuncius.”

Join experts as they uncover the truth behind the find of the century; an alleged proof copy of Galileo’s “Sidereus Nuncius” with the astronomer’s signature and seemingly original watercolor paintings that changed our understanding of the cosmos.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

SECRETS OF THE DEAD is made possible, in part, by public television viewers.

Galileo's Moon

Season 18 Episode 1 | 55m 3sVideo has Closed Captions

Join experts as they uncover the truth behind the find of the century; an alleged proof copy of Galileo’s “Sidereus Nuncius” with the astronomer’s signature and seemingly original watercolor paintings that changed our understanding of the cosmos.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Secrets of the Dead

Secrets of the Dead is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[ Suspenseful music plays ] -The find of a century: a proof copy of one of the most important books in the history of science... ♪♪ ...complete with paintings by the book's author, himself, one of the greatest scientific minds of all time... ♪♪ [ Suspenseful music climbs ] Galileo Galilei.

[ Suspenseful chord strikes ] A discovery that set the rare book market abuzz.

-If it were true, I thought that this would, would really change the historical record.

-How great would that be, if there were a copy of "Sidereus Nuncius" that had Galileo's own paintings in it?

Wow!

I would love to see that.

-When it was published in 1610, the book opened up the universe to humanity.

-It implied a different scale of the universe than had been commonly believed before that.

It was an exciting piece of news.

Nothing like this had ever been published before.

-But, even after the proof copy was authenticated, questions remained.

-Interpreter: In terms of value, the market is constantly growing and the means of creating forgeries and fakes are constantly improving.

-You generally assume that the things that look old, smell old, are old, and, generally, we don't live in a state of constant skepticism, where we're constantly questioning, you know, "Is this genuine?"

♪♪ -Books by some of the greatest minds in history, forged, to be sold for small fortunes.

♪♪ But more than money is at stake.

These works are the very basis of our system of knowledge.

If the books can't be trusted, can the knowledge inside?

-I'm a historian and, if people start messing with the tools of my trade, then I get angry and have to do something about it.

♪♪ -"Galileo's Moon."

♪♪ [ Suspenseful chord strikes ] -Rare books can fetch hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of dollars.

♪♪ They are a tangible piece of history and knowledge.

♪♪ -It's 1631.

-It's a unique book.

-This is 1478.

St. Ignatius was reading this when he had his conversion and found the word "Jesuit" in here, used for the first time.

-This was a pharmaceutical manual, created specifically for doctors in the 14th century.

It's unique because it was made for one person, preserved in its original binding.

-So, this is 550-year-old paper and you can hear it and see it.

-With the dotcom boom and vast fortunes being made very quickly, people are looking for some kinda culture to buy and what kind of culture do they wanna buy?

Tech culture.

And what's tech culture?

It's the history of science.

So, things like Newton, Copernicus, Galileo.

-The book is US$200,000.

-This is $35,000.

-You have something by Einstein, by Isaac Newton, by Copernicus.

I mean, these are things that changed the world.

♪♪ -Galileo Galilei's works are always popular, especially his masterpiece, the "Sidereus Nuncius," the "Starry Messenger."

-The "Sidereus Nuncius" is an announcement of the most exciting news imaginable.

It's a really thrilling book.

-Interpreter: The "Sidereus Nuncius" is an unusual work, very unusual.

Only 550 copies in total were printed.

Of these 550, today, with certainty, we are familiar with no more than 100.

-The market price for a good first edition, depending on its condition, varies between $300,000 and $500,000.

But its worth goes far beyond the price.

In 2005, a previously unknown copy was brought to rare bookseller Richard Lan, one of the owners of Martayan Lan in New York City.

It created a sensation that moved beyond the insular world of rare books.

♪♪ Galileo's "Sidereus Nuncius" has a special place in the history of science.

-"Sidereus Nuncius" is important to everyone because it's one of the few really revolutionary books that have ever been written.

It's changed the way that we think about the cosmos in about 60 pages, as though you're witnessing exactly what he saw 400 years later, which is a pretty moving experience, as well.

[Wind blowing] -But it radically shook up what seemed to be accepted truths of all kinds.

-The day after it was published, someone sent it off to the king of England.

It was immediately seen as a startling revelation that everyone should know about as quickly as possible, especially people in high places.

♪♪ -1610.

Galileo Galilei is 45 years old and lives in this building.

He is a professor at the University of Padua, where he teaches a number of subjects.

By this point in his life, he's already constructed an early thermometer, designed and improved a proportional compass, and he's built a telescope for himself and turns it toward the night sky.

[ Suspenseful chord strikes ] [ Wind blowing ] [ Tranquil tune plays ] "Forsaking terrestrial observations, I turned to celestial ones and, first, I saw the Moon from as near at hand as if it were scarcely two terrestrial radii away."

♪♪ The five etchings in "Sidereus Nuncius" are based on the drawings Galileo made while looking through the telescope.

[ Chorale joins ] -You're brought close to being in the print shop where Galileo was delivering his manuscript.

It's as close as you can get to sitting next to Galileo and looking through a telescope with him.

-"From observations of these spots repeated many times, I have been led to the opinion and conviction that the surface of the Moon is not smooth, uniform, but is uneven, rough, and full of cavities and prominences, being not unlike the face of the Earth, relieved by chains of mountains and deep valleys."

♪♪ -Galileo's observations are the foundation of our basic understanding of the universe.

The Sun, encircled by orbiting planets, is at the center, and not the Earth.

-Before 1610, it was generally accepted that the universe was centered on the Earth, that God had made the Earth, made humans on it, and we were the center of everything.

After 1610, you have this empirical evidence that maybe the Copernican hypothesis, of the Sun being the center of rotation of the universe, is physically true.

-Galileo's drawings upended the worldview that had lasted for at least two millennia.

[ Suspenseful music plays ] In 1543, Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus questioned the idea that the Earth was at the center of the universe, but couldn't provide proof.

Galileo did.

-The universe was changing and this book was the agent of that change.

It has a kind of deeper psychological impact, I think, about where we are in the universe and what our -- whether we're anything special.

It starts to shift humanity from its central, God-given position, physically, at the center of the universe, to a more marginal position, where we are third rock from the Sun, hurtling through space.

It opens up a whole load of new questions about what it means to be human.

♪♪ -After observing the Moon, Galileo shifted the telescope and was able to see Jupiter.

♪♪ [ Pen scraping ] -"On the 13th of January, four stars were seen by me for the first time, in this situation relative to Jupiter.

Three were westerly, and one was to the east.

They formed a straight line, except that the middle western star departed slightly toward the north.

On the 14th, the weather was cloudy.

♪♪ On the 27th of February, four minutes after the first hour, the stars appeared in this configuration.

The easternmost was 10 minutes from Jupiter; the next, 30 seconds."

-Galileo had seen three of Jupiter's moons, effectively proving the Earth was not the center of the universe.

-He realized that the implication of that was that they were rotating around Jupiter and nobody's conception of the solar system, or the universe, in general, had ever allowed that planets have smaller bodies revolving around them.

♪♪ -When it came to the moons of Jupiter, [laughing] there was just no precedent for explaining it and he's open about his amazement, his befuddlement, at first, how to make sense.

It takes a couple of days for him to come to, "Wait a minute, there are -- there are bodies moving around Jupiter.

There's no other explanation."

♪♪ -His observations of both Jupiter's satellites and the imperfect surface of the Moon would ultimately contradict Church teaching.

In 1616, six years after "Sidereus Nuncius" was published, the Roman Inquisition banned heliocentrism, the belief that the Earth revolves around the Sun, from being taught.

[ Sinister chord strikes ] Horst Bredekamp has studied Galileo for 20 years and continues to marvel at how quickly the astronomer published his treatise: just months after his initial observations of the Moon.

♪♪ -[Speaking German] -Interpreter: When he sees that Jupiter has moons, that we're not the only planetary system, he decides, "I'm going to make a book."

-[Continues in German] -Interpreter: He knew that whoever would be the first to print the formulation on a sheet of paper, dated... -[Continues in German] -Interpreter: ..."The Earth is like the Moon.

The Moon is like the Earth," would have formulated one of the greatest revolutions in astronomy history.

[ Suspenseful chord strikes ] -Galileo continued to study and sketch the Moon and stars, even after printing had begun.

-He was in such a heat to get the book published that the end was more or less a first draft, while the book was on press, so that he was revising and there's extra material.

He knew he was on to something gigantic and he wanted to have his name on it.

-Interpreter: Galileo changed the title while they were in the process of printing.

He gave the Inquisition, which had to allow the book to be printed, a different title than the final one.

-[Continues in Italian] -Interpreter: During the day, the printer printed what he had been busy formulating throughout the night.

♪♪ -Interpreter: On March 3rd, he makes his final examination and, on the 10th or the 11th, the book is available: a speed that, even today, remains unbeatable.

♪♪ -The result is a masterpiece that rewrote the entire understanding of man's place in the universe.

[ Bell tolling ] Harvard professor Owen Gingerich is a noted astronomer and is also extremely knowledgeable about rare books.

-I get consulted by the FBI, every once in a while.

Probably, I shouldn't be too talkative about this.

-The professor likes to visit Harvard's oldest telescope, built in 1847 and the largest in the world at the time.

Gingerich understands the doors Galileo opened for him, as an astronomer, and marvels at how luck and timing affected the discoveries in "Sidereus Nuncius."

-What happened was that the Moon was reasonably close and so, apparently, he figured, after looking at the Moon, he would have a look at Jupiter because it was close.

And, lo and behold, he could see the little satellites and this wouldn't have been possible, if he had done it six months earlier.

-Gingerich is often asked to authenticate rare books and remembers the day in 2005 when the Martayan Lan copy of "Sidereus Nuncius" was placed in front of him.

-Richard Lan, who is a New York rare book dealer, I had known him for a long time and he brought two Italians with him, who had this book for sale.

So I started looking at the book and, right at the beginning, there is Galileo's signature.

♪♪ -The book was signed and dedicated by Galileo, himself: "Io, Galileo Galilei fecit," "I, Galileo Galilei, made this."

-There aren't that many books which Galileo signed.

-The book also had a stamp from the library of Prince Cesi, founder of the Accademia dei Lincei, which was dedicated to scientific exploration.

Galileo himself was a member of the academy.

Both items made the newly found manuscript even more exciting, but were insignificant, compared to what Gingerich saw next.

-As we turned the pages of this book, the striking thing was the drawings of the Moon.

Only, instead of being the etchings, these were obviously watercolors, as if this was a very early stage, and, therefore, singularly valuable.

-Was it possible the book was an early proof, printed before the etchings of Galileo's drawings of the Moon were ready, one to which Galileo himself had added his own watercolor paintings of the Moon?

-There are authentic surviving copies of "Sidereus Nuncius" that just have blanks where the Moon etchings should be.

-Interpreter: It made headlines throughout the entire world.

An original manuscript with drawings by Galilei had been found.

-Interpreter: It contains original watercolors by Galileo.

What an exceptional document!

It's like finding an extremely important and previously unpublished manuscript!

-Interpreter: Yes, number zero, the galley proof, the very first copy.

In other words, in 100 years, there hadn't been a find of this magnitude.

-What made it spectacular was that it had Galileo's signature on it.

It had these drawings, supposedly in Galileo's hand.

it had a library stamp linking it to the Lincean Academy.

-Interpreter: If real, it would be an exceptional document and one that would fetch extraordinary prices.

-[Speaking German] -Interpreter: You have to imagine, his signature, "Io," "I," "Galileo Galilei fecit," "I have made this."

The pride emanating from that.

All that created such a sense of immediacy.

Galileo's aura was closer to those in that room than it had ever been before, thanks to that book.

And that really made an impact on people -- on me, as well -- and fascinated them.

That secured the book's renown around the world.

-The men who brought the book to Richard Lan claimed it had been lying untouched for centuries in Argentina before they found it and offered to sell it.

-Interpreter: You can see how the ink here penetrates through to the other side.

Everything appears to add up.

Here, in exactly the same way, the other books have etchings at precisely these points.

And then here, on this page, the depictions of Jupiter and its dancing moons begin.

-[Continues in German] -If genuine, the estimated market value?

$10 million.

-[Bangs gavel] -At the time, most rare book dealers did not worry too much about forgeries because of the labor involved in making a believable fake.

-It had generally been assumed that you couldn't successfully forge 17th-century books.

17th-century books are produced using bits of metal type and a hand press and there are just too many physical factors that are difficult to recreate, nowadays, to make it worthwhile.

-The letterpress printing process would require the creation of identical versions of each letter and punctuation mark that appears on every page.

And then, the forger would have to match the exact spacing between every letter in the book.

Book dealers put great stock in the belief that their products simply couldn't be forged.

In addition to the tedious labor involved, the pages in early modern books have a unique characteristic that rare book dealers believed was difficult to duplicate.

-Most forgeries of early modern books have been done lithographically or using laser jet.

Neither of those printing techniques leaves any print impression in the page.

The Martayan Lan copy had this deep impression, so, almost instinctively, when you look at it and feel it, it looks like a genuine 17th-century book and it doesn't look like a facsimile.

-It seemed unlikely that anyone would create a copy of "Sidereus Nuncius" as believable as the Martayan Lan copy, but it still needed a thorough scientific examination for authentication.

Bredekamp put together a team of international experts that would analyze every aspect of the book: paper, ink, binding.

Until this point, only copies of the Gutenberg Bible had been examined so carefully.

It was sent to the Federal Institute of Materials Research and Testing in Berlin, which examined the Dead Sea Scrolls, paintings by Durer, and texts by Bach.

For three days, the Martayan Lan "Sidereus Nuncius" was subjected to an analysis of all its materials, using infrared light, 3-D microscopes, and X-ray fluorescence.

♪♪ -Interpreter: At the moment, we are measuring the paper and elements such as potassium or calcium are to be expected.

If it were modern paper, one would also expect to find barium and titanium.

-These techniques allowed for a noninvasive analysis so that, crucially, not even a tiny scrap of paper needed to be removed.

-The most concrete test that you could do would be to cut a square inch of paper out and burn it and do a carbon-14 test.

Nobody wants to do that 'cause, if you've got a genuine book, you're now missing a square inch of it.

-Interpreter: If we had found elements, materials, or substances that had not fit with those of the 17th century, we would have immediately said it was a fake or a copy.

-[Continues in German] -Interpreter: The most important question concerned the watercolors, for they are extremely unusual in this book.

And what we learned is that it was an organic material, most likely a kind of bister ink, which is not unusual for the 17th century at all.

-Scholar Paul Needham was a part of Bredekamp's team in Berlin.

-And so I was going to write a chapter about the printing of "Sidereus Nuncius," the physical process of printing, producing, the 1610 edition.

And so it turned into just a great opportunity to deal with both this book and with early 17th-century printing, with the book trade, so on and so forth, and so it was a very enjoyable couple of years of intense study.

-The various elements all seemed to point to one thing: the book and its watercolors were genuine.

-It is unique.

It is a unique -- It is a unique book.

♪♪ -Spring 2012.

-[Speaking Italian] -While Bredekamp and his team in Berlin finished their examination, the director of the Girolamini Library in Naples was arrested.

Under the pretext of renovations, he had been stealing thousands of valuable volumes from the Renaissance library for months.

His name?

Marino Massimo De Caro, ex-bookseller, and protégé of Prime Minister Berlusconi's culture minister.

Vito de Nicola is the current director of the Girolamini.

-Interpreter: This is what a lot of the library's rooms looked like.

This was the entrance hall.

The books were heaped in piles near the door because, every so often, a van would come at night to steal them.

♪♪ -Today, it is still unclear just how many books disappeared under De Caro's watch.

Many catalogues were simply destroyed.

♪♪ -Interpreter: An architectural book that managed to escape the massacre.

♪♪ Here, some pages are missing.

These pages generally have illustrations.

They've been cut out and sold individually.

♪♪ -[Speaking Italian] -Interpreter: Mr. De Caro was sentenced in accordance with the allegations against him.

-[Continues in Italian] -Interpreter: It was a serious blow that the very person who committed the crime was the same person who had been responsible for protecting the heritage of that extraordinary library.

-[Continues in Italian] -Interpreter: The Girolamini Library was the first public library in history.

Its reading room is probably the most beautiful in the world.

-[Speaking Italian] -Interpreter: My colleagues here continue to view De Caro as one of the worst of all delinquents because he is such an expert, when it comes to books, to cards, but, at the same time, so incredibly attached to the economic value of these objects.

♪♪ -In 2012, Massimo De Caro was sentenced to seven years under house arrest.

His case shocked Italy and rare book dealers all over the world.

[ Bell tolls ] The National Library of Florence owns the majority of original Galileo texts and received requests from De Caro.

Before coming to the library in Naples, De Caro, as special advisor to the cultural minister in Rome, paid a number of official visits to national libraries.

Library curator Susanna Pelle remembers meetings with De Caro.

-[Speaking Italian] -Interpreter: In the world of research, there were already, there were doubts about Massimo De Caro.

-[Continues in Italian] -Interpreter: Whenever he came to the library, the fact that he came accompanied, earlier than expected, always expected to be welcomed... -[Continues in Italian] -Interpreter: ...there was something a bit... dubious about it all.

-Presumably, De Caro looked at these materials.

We do know that he was very interested in the Galileo collection and, at one point, actually, when he had a position in the Ministry of Culture, was trying to get the entire Galileo collection -- 350 manuscript volumes like this, plus a load of printed books -- sent to Rome to have them redigitized.

Luckily, the National Library here refused that request.

Who knows what would've happened if this entire collection had gone to Rome?

It's very unlikely that all of it would've come back in the same condition.

-Historian Nick Wilding is another scholar of Galileo's work.

[ Tender tune plays ] In 2012, he was writing a review of a book about the Bredekamp team's research on the Martayan Lan copy.

♪♪ Now, several years after his work on "Sidereus Nuncius," Wilding has come to the National Library of Florence to see their two copies of the book.

-This is the first time I've handled this manuscript.

I've looked at online reproductions a lot.

We have the famous observation notes, where Galileo, for the first time, sees the satellites of Jupiter: one of the most exciting documents in the history of science.

You see the night sky here.

He was very interested in why the dark part of the Moon at night wasn't as dark as the night sky and it's because light is reflected from the Earth.

So he's very careful to make the dark side of the Moon a little bit lighter than the night sky.

[ Suspenseful music plays ] -Working on his review, Wilding studied the research and online copies of the "Sidereus Nuncius" and began to have doubts about the Martayan Lan copy's authenticity.

Here, we had something that seemed to be Galileo's own copy, with his own drawings in it, with a provenance relating it to the first scientific academy in the world.

I mean, this is hot stuff.

You want it to be true.

-He learned that, in 2005 and 2006, several rare Galileo works came on the market, all bearing the same stamp from Cesi's library.

-If you just went and looked at examples of this same stamp in other library collections, where they'd been for hundreds of years, you found that that line was always broken.

If you looked at any copy that had come on the market since 2005, this line was always intact.

♪♪ I thought, "Well, perhaps this is, at some level, a fake."

Now, there are multiple levels at which an object like this could be sophisticated or forged.

It's not all or nothing.

-Wilding believed the stamp was applied much later.

-But that seemed a weird thing.

If the Galileo inscription was genuine and the Moon pictures were genuine, why would you jeopardize the value of this great, already great, book by putting a fake library stamp on it, which is relatively easily traceable?

And my initial working assumption was that this was a genuine copy of the "Sidereus Nuncius" which lacked the illustrations.

There are 10 other copies like that in the world.

So you get a real thing and then you put in a fake library stamp.

You put in the inscription.

You put in the drawings and it's suddenly worth 20 times as much as a normal copy.

That makes good business sense.

Even though it's a criminal.

It's still an act of forgery.

♪♪ -The historian then turned his eye to the Galileo signature.

♪♪ -Everyone's signature changes over their lifetimes, but we have examples from Galileo's correspondence and from one other copy of the "Sidereus Nuncius" with a dedication, where we know exactly what Galileo's signature looked like in 1610.

-The signature on the Martayan Lan copy is Galileo's, but it's from his recantation before the Inquisition in 1633, 23 years after "Sidereus Nuncius" was published.

♪♪ After several more weeks of research, Wilding found additional anomalies in the text of the Martayan Lan copy.

♪♪ With that evidence, Wilding contacted Paul Needham.

-I'd been in correspondence with Nick Wilding for a couple of years, about miscellaneous questions in and around Galileo.

And I knew that he had some doubts that he didn't fully express, but I kinda knew they were there.

And I saw this message from him and he said that, in November 2005, an auction house in New York offered for sale a copy of "Sidereus Nuncius" in one of their auctions.

And he said the title page was just like that of the Martayan Lan copy, which had a couple of peculiarities on it.

This kinda came out of nowhere, but there should not be another copy that has these peculiarities because, theoretically, that Martayan Lan copy was a proof copy, made just for Galileo at an early stage of production.

The only way to do this is to put it side by side with a definitely authentic copy and the copy to do it with was, of course, the copy at Columbia and, after about 20 minutes, I saw disparities, having them alongside each other.

Specifically, it had not been printed from movable type and, of course, for a book in 1610, that's the only way to print a book, so it had to be wrong.

I said that, "I think that, putting our thoughts together, we have absolute proof that it's a forgery," [ Melancholy tune plays ] and, yes, it is a forgery.

-Once Needham agreed the book was a fake, Wilding sent a difficult email to Bredekamp himself.

-[Speaking German] -Interpreter: The worst moment was when i realized the import of Nick Wilding's email.

-[Continues in German] -Interpreter: That was here, at this table, in this room.

-[Continues in German] -Interpreter: And, based purely on the logic of what he had written me... -[Continues in German] -Interpreter: ...within a short time, I intuitively saw no way of refuting his suspicion.

-[Continues in German] -Interpreter: The ground just opens up beneath your feet.

That was one of the worst moments in my consciousness.

Let's put it that way.

[ Suspenseful music plays ] -The work of the century was a fake.

[ Suspenseful chord strikes ] [ Vehicle horn blares ] Bredekamp brought his team together for a second time.

The scholars wanted to understand how they were tricked.

Richard Lan, still the book's owner, agreed to let the book undergo a second analysis and, this time, the team would be allowed to take paper samples.

-[Speaking German] -Interpreter: Once we were allowed to take paper samples, it was pretty simple: The paper had been produced in the 20th century.

But, to see that, we needed the samples.

That had not been allowed the first time we conducted our measurements.

-In 2014, Bredekamp made an announcement.

[ Indistinct conversations ] -[Speaking German] -Interpreter: Up until three years ago, I did not think it was possible to fake a book.

This is the first case.

-[Speaking German] -Interpreter: I'd like to start off by showing you the object... the demon.

[ Laughter ] This book was presented to me in 2005.

Naturally, it had been declared authentic by the dealers in America, as an original.

-[Continues in German] -Interpreter: What might have also played a role was that, until a few years ago, it just wasn't considered possible to forge a historical book, at all.

-The researchers explained what Wilding found: tiny printing mistakes that would've been impossible in the 17th century revealed the forger's 21st-century efforts.

-[Speaking German] -Interpreter: What led Nick Wilding, the very first person to do so, to recognize the book as a fake?

A single little spot.

And that was the moment in May 2012.

It hit us like a brick.

♪♪ -The title page of the Martayan Lan copy has a spot next to the P in Privilegio.

It matches a spot that appears on a commemorative version that was published in 1964, in the city of Pisa, but not on any first edition.

Needham also noticed something odd about the Latin word periodis on the title page of the Martayan Lan copy.

-There's the Latin word periodis, like our word period, meaning the periods of rotation.

And, in the Martayan Lan copy, instead of p-e-R-i-o-d-i-s, it was p-e-P-i-o-d-i-s, which, sort of theoretically, would've been a typographical error of the compositor.

Any compositor eventually makes some typographical errors, here and there.

And the idea that there is a second copy with that same typographical error, which didn't appear in any of the other many copies that I'd examined, both by facsimile and in the original -- that is, by photographs and in the original -- that just didn't make any sense.

-But what about the belief that it was impossible to forge an early modern book because of the type impressions?

-They assumed that a forger would have no type impression, whatsoever, and that it would just be flat on the paper.

So, all of these forgeries have this deep ink impression and so it was just assumed that they were genuine.

But if you talk to a printer and say, "How would you go about doing a forgery?"

They say, "Oh, it's relatively easy."

-Such a believable fake is the result of new printing methods.

-It's become extremely common, now, to use photopolymer plates, which are a kind of light-sensitive plastic.

You expose a negative, expose a plate with a negative over it and bits of the plate harden and the rest, you wash away, and you're left with a relief plate.

When you print on it, it gives exactly the same kind of deep letterpress impression as printing with type.

-Photopolymer plates create the indentation on the paper that rare book dealers assumed indicated a genuine book.

-So, when you're making your forgery, you press them into the paper and it makes deep-ish impressions into the paper, which, at first, looks authentic because that's what printing types do.

-But they can also leave evidence on the page that reveals the forgery.

-When you put a piece of paper down onto that inked type and then push down, what you frequently find is that, while the letters leave a deep impression, as well as inking, little bits of ink also just touch the paper and you get these little lines around the -- especially around the tops and bottoms and sometimes in the margins.

But usually in the tops and bottoms of a 17th-century book, you see these very faint printer's ink lines.

-One can see these lines on the pages of the "Sidereus Nuncius" at Columbia University's Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

-Right here is the shoulder ink and, because it's right at the edge, when they stamped the ink, a little bit of ink got caught there.

But that ink is just like a little trace and so it's picked up in the printing process.

-There's no force behind those.

There's no impression because there's nothing sticking up.

There's just where the paper's touched the bits of ink that've been caught between the spacing bars.

So, the question is: If you take a photograph of a printed page and you don't white out those, what we call shoulder inking, and then you turn that photograph into a three-dimensional plate, it occurred to me that what one should find is that those, those little bits of inking get turned into a three-dimensional object, in the same way that any typographical character does.

And then, when you print from that, you should get an impression of this incidental inking.

And that's impossible with typography, but it should be -- The prediction was that one should find that, if one's looking at a forgery made with photopolymer plates.

-The spot next to the P in Privilegio, with its deep impression on the page could only have happened with a photopolymer plate.

♪♪ Once deemed impossible, forging 17th-century books was now a reality, but once the book was proved a fake, questions remained.

♪♪ Still serving his sentence for his theft of the books from the library in Naples, Massimo De Caro lives in Verona, with his wife and two German shepherds.

-[Barks] -The house is filled with a collection of items related to Galileo and the exploration of space.

-[Speaking Italian] -Interpreter: This house mirrors me and my passion for Galileo Galilei, a passion I have transferred to my wife.

-[Continues in Italian] -Interpreter: Here are the autographs of all 12 astronauts who were on the Moon.

-[Continues in Italian] -Interpreter: This one is a reproduction of the portrait of Matteo Barberini, when he was still a cardinal.

Later, he would become Pope Urban VIII: as we all know, the one who would sentence Galileo.

♪♪ -[Continues in Italian] -Interpreter: This suit was worn by the Russian cosmonaut Frienko during his mission on the Mir space station.

-[Continues in Italian] -Interpreter: I have a collection of facsimiles of the "Sidereus Nuncius."

Let's have a look at this one.

But I have to say something: They're not as beautiful as the one I made.

This is a facsimile of the "Nuncius" made in 1977, but, when you touch it, you don't feel a thing.

What I mean is the book is cold.

Now, if you take this book and allow the paper to sing, the paper sings.

Do you hear it?

[ Rattling ] -[Continues in Italian] [ Sniff ] -Interpreter: Unfortunately, you can't smell it.

[ Rattling ] This book sings.

This book speaks.

This book transmits something to us.

It's not dead, like this modern book.

♪♪ -De Caro readily admits he create the forged copy of the "Sidereus Nuncius" with the watercolors.

♪♪ -[Speaking Italian] -Interpreter: I had a "Nuncius" that I bought in Argentina.

It served as the basis for my own work.

-[Continues in Italian] -Interpreter: I jokingly refer to it as my kid because, to be honest, I even brought it to bed with me and leafed through it [chuckle] before going to sleep.

I truly consider the book I produced to be a living creature.

The whole thing took me more than three years.

Three years!

But, if I'm going to be honest, I had so much fun.

♪♪ -The photopolymer plates made quick work of "Sidereus Nuncius's" text, but De Caro found it difficult to create believable copies of the etchings.

-[Speaking Italian] -Interpreter: I tried to make etchings of the Moon because I wanted to make a normal copy of the Nuncius.

-[Continues in Italian] -Interpreter: But then I realized that the appearance of the modern etchings made on paper wasn't all that great.

♪♪ -The 21st-century technology that created the forged book couldn't make believable 17th-century etchings.

♪♪ -It wasn't complicated, but you could see that they'd been made today.

There was no way to age them properly.

I had to find something to distract one's eyes from the print, and so I came up with the idea of making the moons.

The story I wanted to come up with for this copy was that it was one of the 25 without any Moon etchings, but that later, in the 18th century, the owner decided to complete the book by making watercolor moons.

The circle of the Moon was drawn with a red-wine glass, which had precisely the right dimensions.

But when I learned that the person who'd helped me make the moons could also emulate calligraphy, I decided, "Let's go ahead and take the leap.

Let's set the words 'Io Galileo Galilei fecit' on the title page."

And I have to say, it worked.

♪♪ -And the stamp from the Cesi Library?

-Here we are.

As you can see, this is the very same stamp you see on the "Sidereus" -- the circle with an unbroken line.

-De Caro claims again and again that all of the mistakes in the Martayan Lan copy were made on purpose, as if his work had been an intellectual prank to test academics and antiquarians.

These claims could help protect him from legal charges of fraud.

He takes pride in the fact that he was able to fool so many.

-That was the moment of truth.

Now I'd find out if I'd done a good job.

Now we'd see whether the experts would find the breadcrumbs I'd left behind in the woods, but, no, they didn't find the breadcrumbs.

It's like with a magician.

When he comes onstage, the magician gives the audience something to see in order to cover up his own tricks.

But I didn't create a fake "Nuncius."

I created a different "Nuncius."

And that's the problem.

I created a different "Nuncius."

The problem is the fake historians who did not recognize that it was a reproduction.

-Wilding doesn't believe De Caro's claims.

-But we must never lose track of the fact that this was done for cash.

You know, this was a book that was gonna sell for $10 million, and that's the only point that it exists.

All the stuff that De Caro said about, you know, this being an intellectual challenge, a hoax that reveals how experts don't know what they're talking about, that's just kind of retrospective attempt to dissipate the seriousness of what he's done.

He's committed fraud on a massive scale, and he's done it for money.

-This is a book which automatically is worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Whatever he might say, the motive is essentially a financial one, and, of course, he did sell it successfully to a dealer.

♪♪ -Horst Bredekamp is haunted by the mistaken authentication.

-Neither the group nor I were able to recognize the book as a fake.

This is a humiliation... which is presumably comparable to a very serious error by a doctor.

♪♪ For the public must be able to trust that an art historian can differentiate between a fake and an original.

This is a trauma.

These are real copies of the "Sidereus Nuncius" which I procured.

-Bredekamp and De Caro even traded emails once the forgery was discovered.

-In my correspondence with him, there is the unbelievable sentence, "Dear Professor, it must have seemed as if, once you had the drawings of the fake 'Sidereus Nuncius' before your eyes, you were being confronted with the results of your own work."

In other words, the forger used my very own research, and that just floored me.

That explains why I simply did not want to recognize, or perhaps could not recognize, the fake as a fake.

-I feel a bit guilty, because, in some ways, I was inspired by him.

-Paul Needham had a different reaction.

-Oh, I felt great.

I felt great.

I mean, just...

I was so glad that I hadn't gone on believing something false.

To me, it was just thrilling to be able to sit with these two books and find things that really count as proofs.

-The forged "Sidereus Nuncius" caused immense damage to the antiquarian book market.

-Many institutions are refusing to buy anything that is coming from Italy, so it had a very negative effect.

-People would become concerned that they were going to end up buying a fake or something stolen, and all you have is your reputation, because people can always buy from somebody else.

-Many dealers continue to consult Owen Gingerich.

-De Caro is getting out of arrest in a few months.

-Really?

-Mm-hmm.

-What do you think he's gonna do when he gets out?

-[ Chuckles ] -Go back to the old hobby?

Have you received a personal invitation to his coming-out party?

-They are very much worried to have De Caro loose again.

Who knows what he has squirreled away and what he will be up to?

♪♪ -In the meantime, many large libraries, museums, and foundations have been asking themselves whether some of their stamps, drawings, or even entire books could be faked.

♪♪ -This book is a very good fake -- the structure of the layers, the structure of the paper, the structure of the watermark, but it's not the only fake that exists, and I assume it won't be the last.

-We thought that our case would be enough of a wake-up call for someone in the world to create a database of fakes.

As far as I know, that has not been the case.

-De Caro, one hopes, will not make more forgeries, but other people will.

This is a cheap technology.

I myself could forge an acceptable "Sidereus Nuncius" for a few thousand dollars.

-It's like doping.

Along with the ability to detect doping drugs, new, undetectable drugs arrive.

Doping and forgeries are the same -- in terms of methodology, in any event.

-The story is not over, it's ongoing.

And in a bigger sense, the story is ongoing because the techniques and technologies that Massimo De Caro used are still with us.

And there's nothing illegal in replicating a 17th-century book, right?

So we're gonna see a lot more of this.

It's really -- it's getting to be pretty easy to make a forgery now.

Once you start admitting forgery, or saying basically that the market can decide what's true and what's not and that if the market wants the forgery to be true, it is true, then that's fundamentally pretty disturbing, because then truth is for sale.

-And for Wilding, fake books lead to false history.

-Well, history just matters.

If you start fabricating the objects, then you might as well fabricate an entirely different, alternative history, and from there, you can start denying major historical events, you can rewrite history -- you're in an Orwellian world where political power governs truth.

And I think one of the first victim of that is the general public.

-The forging of books remains far less lucrative than creating fake Picasso paintings or Giacometti statues.

But what do these technologies mean for the rare-book market?

-How much longer will this market last?

I cannot make any predictions.

I can only express my personal attitude.

For a long time now, I haven't bought any books on the antiquarian market.

-The publication of "Sidereus Nuncius" in 1610 ultimately led to Galileo's arrest and trial by the Inquisition in 1633.

-He was a lightning rod for people who were interested in his work and people who didn't like what he was doing because it's hard to give up what you've thought all your life and what has history and the general opinion.

-Galileo's influence remains immeasurable four centuries later.

♪♪ -That was the beginning of cosmology as we still know it today.

-I think that these Galileo documents still have something to say.

They continue to transmit this desire to know.

I think this is what drives our societies forward, and, above all, this is the most important thing, the very heart of the human being.

-Galileo's voice comes out very, very loud and clearly over more than four centuries.

We have this conversation that he enabled by leaving this mass of papers and writings and drawings and artifacts.

-Ignition sequence start -- 6, 5, 4, 3... -Our modern space program owes its own debt to Galileo and "Sidereus Nuncius."

-We have a liftoff.

-"Sidereus Nuncius" is the book that showed that the Moon was a place you could go to and stand on when you got there.

-Both hands stand about the fourth rung up.

-With a little guidance, our theoretical Galileo would have gotten himself up to speed with today's science very quickly.

[ Beep ] -And on the Apollo 15 mission, the astronauts paid tribute to him.

-Commander David Scott did Galileo's experiment on the Moon.

-Well, in my left hand, I have a feather.

In my right hand, a hammer.

I guess one of the reasons we got here today was because of a gentleman named Galileo a long time ago who made a rather significant discovery about falling objects and gravity fields.

And we thought that, where would be a better place to confirm his findings than on the Moon?

And I'll drop the two of them here, and, hopefully, they'll hit the ground at the same time.

How 'bout that?

That proves that Mr. Galileo was correct in his findings.

♪♪ Superb.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S18 Ep1 | 3m 46s | Galileo challenged the widely-accepted belief that the universe revolved around the earth. (3m 46s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S18 Ep1 | 3m 24s | Experts explain how a fake Sidereus Nuncius made its way into infamy. (3m 24s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S18 Ep1 | 30s | Join experts as they examine an alleged proof copy of Galileo’s “Sidereus Nuncius.” (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

SECRETS OF THE DEAD is made possible, in part, by public television viewers.