Finding Your Roots

Forgotten Journeys

Season 8 Episode 7 | 52m 9sVideo has Audio Description

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. helps John Leguizamo and Lena Waithe retrace their ancestral paths.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. helps John Leguizamo and Lena Waithe retrace the paths of their ancestors, uncovering crucial pieces of their own identities that were lost on the journey to America.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

Forgotten Journeys

Season 8 Episode 7 | 52m 9sVideo has Audio Description

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. helps John Leguizamo and Lena Waithe retrace the paths of their ancestors, uncovering crucial pieces of their own identities that were lost on the journey to America.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

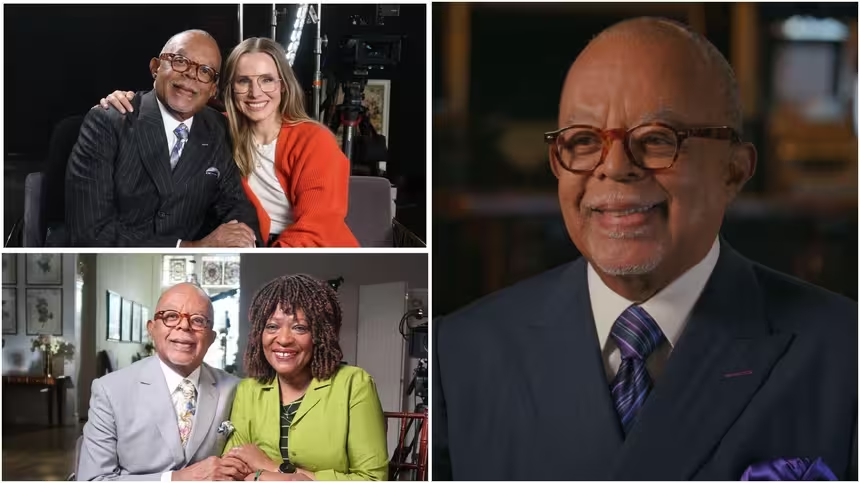

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipGATES: I'm Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Welcome to Finding Your Roots.

In this episode, we'll meet John Leguizamo and Lena Waithe.

Two stars who built their careers by exploring their identities are now going to discover just how complex those identities really are.

LEGUIZAMO: This is my 15th great-grandfather?

GATES: How 'bout that?

LEGUIZAMO: From coming from no history to having so much history is, it's, it's unbelievable.

GATES: You descend from a Native American woman.

WAITHE: What?

GATES: To uncover their roots, we've used every tool available... Genealogists combed through the paper trail their ancestors left behind, while DNA experts utilized the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets hundreds of years old.

And we've compiled everything into a book of life... WAITHE: Wow!

GATES: A record of all of our discoveries... LEGUIZAMO: Wow, that's incredible.

GATES: And a window into the hidden past.

WAITHE: This is crazy.

LEGUIZAMO: I'm getting, uh... uh, teary-eyed here.

Uh, yeah, it's beautiful.

WAITHE: It feels like one big huge blessing to be connected to all of these people.

GATES: John and Lena grew up in the United States, knowing almost nothing about their ancestors who lived far from our shores.

In this episode, they're going to meet those ancestors, retrace their incredible journeys, and uncover the hidden diversity within their own family trees.

(theme music plays).

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ GATES: John Leguizamo is a national treasure.

Over the past three decades, he's carved out a unique path... Juggling leading roles in film and television with his brilliant self-created one-man shows... LEGUIZAMO: Yo Johnny, don't be afraid, come on.

Go Johnny, go Johnny, go, go, go!

Go me, go me, go me, go me, go me.

And I get to the conductor's boof... Boof, that's how I used to talk.

Baf-room, leng-ff, nor-ff.

Yo, we were so ghetto we couldn't even afford a T-H. GATES: On stage, John explores the Latino experience from myriad angles, via a dizzying array of characters.

But it all feels firmly rooted in his own experience, because it is.

When he was four years old, John's family emigrated from Bogotá, Colombia to Queens, New York, where John grew up watching his parents make immense efforts simply to put a roof over their heads.

LEGUIZAMO: My parents were always struggling and striving.

I mean, when we first got here, the four of us, we lived in an apartment that was so small, the furniture was painted on the walls.

And we had a Murphy bed.

I don't know if people, uh, you know, are... GATES: They have no idea what a Murphy bed is, but tell 'em.

LEGUIZAMO: Yeah.

Yeah.

You know, so, it's a bed that's built so that when the day comes, in the morning, you get up, you put it back up... GATES: Right.

LEGUIZAMO: On the wall.

So, you have a living room, dining room, bedroom was all one room.

That was the first year.

The second year, my parents worked their butts off so that they got their own room.

And then eventually, we had a living room separate from the dining room.

And then, you know, every year we moved up 'til we got a house, and then my father rented all the rooms, and we had to live with all these tenants, and we had to like, you know, clean their rooms and do all, and do all kinds of, uh, manual labor.

GATES: What effect do you think that had on you?

LEGUIZAMO: Well, it made me rebel.

It made me rebel against them.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LEGUIZAMO: It made me very anti-authority, because it, it, it was so strict at home, and, and it made me, you know, love humor and comedy, and all I wanted to do was be fun, be around fun, and having fun.

GATES: John's ambitions would quickly grow.

He started out doing stand-up, then discovered more serious theater, and was hooked.

By the time he was 17, he was reading Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller, and telling anyone who'd listen that he was going to become an actor.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this wasn't what his parents wanted to hear... LEGUIZAMO: My father was like: "We didn't come to this country for you to be worse than us."

You know, you, you can't be an actor, don't, you, you know they were, they were horrified.

I mean, first of all, you never see Latin people on television or plays or anywhere, so how are you gonna make a living?

But I didn't care because I fell in love with this, this, this calling, this, this, a higher, uh, art, you know?

I don't know, to me, it was the greatest art the world had ever, ever created, and, and so nothing was gonna derail me.

GATES: John was true to his word... After dropping out of college, he took acting classes at New York's famed HB studio, then set his sights on a career in Hollywood, where he soon confronted a new challenge: typecasting.

The only parts he could get were gang members, drug dealers, or other stereotypes of Latino men.

The dilemma would ultimately fuel his creativity, but not before a great deal of soul-searching.

LEGUIZAMO: How else was I gonna make a living, you know?

And I was hoping maybe this is that, that stepping stone.

Maybe this is that, that thing that's gonna get me to the next better thing.

But it wasn't, it was like...

I would see all the cats.

I would see Luis Guzmán, Benjamin Bratt, Benicio del Toro, and all of us, you know, coming in for gangsters with bandanas, leather jackets, you know, "What's up man, what's up, what's up?"

Or janitors, you know, "Como... how are you doing, how's everything going?

Everything's good."

You know?

So...

I started to create my own stuff.

And that, that rejection of Hollywood, and, and Hollywood rejecting me, forced me to find a new path for myself.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LEGUIZAMO: And I'm grateful for that rejection, because I now create.

I'm self-generating, and uh, I, I was, I've been able to be a voice for Latin kids and Latin people, you know, showing that our culture is valid, that it's viable, and that my ethnicity is my, my power.

GATES: My second guest is actor, writer and producer Lena Waithe, creator of Showtimes' hit series The Chi, a kaleidoscopic look at Chicago's south side.

It's a place that Lena knows intimately.

She spent most of her childhood in the neighborhood... raised by a single mother, who was often too busy to supervise her closely and largely cut off from a father, who struggled with substance abuse...

But while Lena was certainly shaped by the world outside her door, there was another force that was just as strong: her maternal grandmother, Tressie Hall, who lived with her, inspired her, and even introduced her to her future profession.

The two spent hours together in front their television, guided by Tressie's well-formed tastes... WAITHE: We watched a lot of old TV because that's what my grandmother wanted to watch.

Like but... GATES: Because she was old.

WAITHE: Yeah, because she was older.

GATES: It wasn't old to her!

WAITHE: She's like, "I like this TV," you know, uhm, but we'd watch Hunter and Columbo and, like, you know, Maude, and, and All in the Family.

And I just loved her sense of humor, I loved her swag, and I enjoyed that time and, and laughing with her and learning about just how important storytelling could be through television shows.

GATES: Lena's grandmother lit a fire that has never gone out.

After college, Lena moved to Los Angeles, with no connections, and sought work as a production assistant.

The odds were stacked against her, but Lena wasn't thinking about that... GATES: Now, Hollywood is not exactly known to be friendly to African Americans, traditionally.

WAITHE: No.

GATES: How did you find it when you, got here?

WAITHE: At the time there was a Black Hollywood.

It was smaller, but it was, it was there.

And one of my professors said, "If you can land in Black Hollywood, you'll always be okay."

It was like, and so, I said, "Okay."

And, uhm, yeah, my first gig was on Girlfriends, as an assistant to the showrunners, and it was a dream come true.

I was like, "Oh man, this is, this is it.

This is great."

Uhm, and then, of course, a strike hit, and everything kind of just came crumbling down, and I was like, "What am I doing?"

And that's when I think when I got really creative and decided just to kind of write and try to find my voice, and that's what I started to do.

GATES: Was your family supportive?

WAITHE: Yeah, they were.

The, the hard thing for them was that they just didn't have any information, they couldn't really help me because it's just a very tricky business, and they knew they didn't know a ton about it, but they knew that I had a lot of drive, and I was just going to try to figure it out on my own.

GATES: You're hard-headed.

WAITHE: Yes, always have been.

GATES: Lena's unwavering drive has served her well, giving her the confidence to stand up for her own story, onscreen and off.

It's also led to an amazing string of successes.

Since 2017, she's won an Emmy, created three TV shows, and written a feature film.

But for all her accomplishments, Lena remains very much a product of the family that nurtured her dreams from the very beginning... WAITHE: I wouldn't be here if it weren't for their love and their support, and also, you know, some of the dysfunction, and I think without that, I don't have anything to draw, draw from.

It wasn't all, it wasn't a perfect upbringing, it wasn't, you know, it wasn't easy, and because of that, I'm, I have some wounds and some scars that make me the artist and the writer I am.

GATES: Uh-hum.

WAITHE: So, I, you know, it's interesting because I think some people say, you know, they want trauma-free entertainment.

GATES: Good luck with that.

WAITHE: Exactly.

It's like... GATES: Well, there is no trauma-free author.

WAITHE: Yeah, exactly.

And so we have to find ways to heal, and the way I choose to do that is to, to write about things that aren't always pretty.

GATES: Lena and John grew up in homes where daily existence could be a struggle, in families focused on the future, not on the past.

As a result, though each has a strong sense of themself, they have little knowledge of the ancestors who laid the groundwork for their success...

It was time to change that.

I started with John Leguizamo.

Growing up in New York City, far from his native Colombia, John's understanding of his ancestry had been filtered through heavy layer of mythology, as John himself readily admits... LEGUIZAMO: It's all, like, so interesting in Latin America especially in my family, uh, you know, uh, there's so many stories, you know, that, uh, my grandfather was Lebanese, part Lebanese, and, and his wife was Afro Latina, and then my grandmother is an Incan princess... GATES: You sound like, uh, Black genealogy at a family reunion, you know?

Yeah, a king in Africa!

LEGUIZAMO: Yeah.

There's, there's a lot of fablizing about, about the story, but I don't know the real, real deal.

GATES: The "real deal" behind John's family tree would prove fascinating, but it took our researchers a lot of time to untangle it from the "fablizing".

On his mother's side, that meant following the paper trail back almost three centuries, all the way back to John's 6th great-grandfather, a man named Manuel Salvador Londoño... Manuel was likely born in Colombia sometime in the 1720s, the key to his story, and indeed to this entire branch of John's tree, lay in the archives of the city of Rionegro.

LEGUIZAMO: This is wild, my sixth grandfather.

GATES: Great-great-great-great- great- great-grandfather.

LEGUIZAMO: Wow.

GATES: Now, look on the right.

That is part of Manuel's will... LEGUIZAMO: Oh, wow!

GATES: Recorded in Rionegro in 1796.

Would you please read the section of your ancestor's.

LEGUIZAMO: Oh my god.

I hope there's something for me.

I hope there's, I hope there's a piece of land or some money.

GATES: Would you please read the section that we've translated?

LEGUIZAMO: "Manuel Salvador Londoño, natural son of Petrona de la Chica.

He executed his will before Public Notary Dr. Alvarez y Tamayo on April 25, 1796."

GATES: You notice anything different about Manuel as he's described there?

LEGUIZAMO: "Natural son."

Oh, not legitimate.

GATES: Yeah.

Natural.

LEGUIZAMO: Whoa!

GATES: So, at the time of Manuel's conception and birth, his parents were both single and unmarried.

LEGUIZAMO: You know, young people can't control themselves.

GATES: And as you could see, there's no mention of the name of Manuel's father.

LEGUIZAMO: No.

GATES: And of course, this was common for illegitimate children.

LEGUIZAMO: He disappeared, deadbeat dad.

GATES: Let's find out.

Please turn the page.

LEGUIZAMO: Who's the daddy?

GATES: Ordinarily, it would be impossible to identify the unnamed father of an illegitimate child born in the 1720s.

But we had an extraordinary tool at our disposal.

In the 18th century, priests in Colombia often kept notes on events in their parishes.

These notes were compiled by an historian in 2006, providing an invaluable resource for genealogists because the priests had a wide array of interests, and were willing to preserve gossip that was excluded from official records.

Thanks to these priests, we learned a great deal about John's ancestry, including the identity of Manuel's father, a man named Sancho Londoño Zapata.

You ever heard that name?

LEGUIZAMO: No.

I have never.

GATES: Well, Sancho is your seventh great-grandfather, and he was the corregidor of Rionegro at the time, which meant he was the local administrator for the Spanish crown.

LEGUIZAMO: Oh wow, so this is a Spaniard guy.

This is a... GATES: He was a big deal, man.

Your sev... LEGUIZAMO: Yeah.

Yeah.

GATES: Let me tell you how big he was.

Your seventh great-grandfather, when he died in 1765, was the richest person in the entire province.

LEGUIZAMO: No.

Get out of here.

Where's my money?

GATES: He was the corregidor.

That was his title.

LEGUIZAMO: Yeah.

Yeah.

That's incredible.

That's incredible.

GATES: Though John's 7th great-grandfather was a powerful official, we know little about his life, and nothing at all about his relationship to John's 7th great-grandmother, a woman named Petronila de la Chica Betuma.

But turning back to the compiled notes of Rionegro's priests, we discovered something about Petronila... She was a Native American.

LEGUIZAMO: "Teresa de la Chica Betuma was daughter of Miguel de la Chica, Indian."

Oh, I had a feeling, and his wife Francisca, he, he liked the flavor, a little.

"And his wife, Francisca Betuma, a marriage celebrated in Rionegro in April of 1673."

That's nuts.

At the same time, Francisca was the daughter of don Jeronimo Betuma, noble Indian of El Peñol.

The daughters of Miguel de la Chica and Francisca Betuma were Petronila de la Chica and Teresa."

GATES: John, according to this source, your seventh great-grandmother was Indigenous.

LEGUIZAMO: Yeah, yeah, but I knew, uh, look at me.

Yeah.

GATES: Yeah.

LEGUIZAMO: It came from somewhere.

That's wild.

GATES: And this introduces us to her parents, who are your 8th great-grandparents, Miguel de la Chica and Francisca Betuma, who are both recorded there as being also Indigenous.

LEGUIZAMO: Yeah, In, they just say Indian.

Isn't that wild?

They just say Indian.

GATES: Yes.

You've also read the name of your ninth great-grandfather, Jeronimo Betuma.

LEGUIZAMO: I can't believe we got a ninth, a ninth grandfather.

What, are you going to go to the beginning of time, I mean?

From coming from no history to having so much history is, it's, it's unbelievable.

GATES: And read again how he's described.

LEGUIZAMO: "Noble Indian."

GATES: "Noble Indian."

LEGUIZAMO: That's beautiful.

It's very moving.

I mean I'm very, I'm, I'm, I'm moved.

I'm getting uh, uh, teary-eyed here.

Uh, yeah, it's beautiful.

I mean to... (Sighs).

GATES: What's it like to see that?

LEGUIZAMO: Well, I feel very proud, and I mean it's incredible to know that that's where I get my Indigenous blood from.

It's a, the direct name, the direct person.

GATES: We believe that Jeronimo, was likely born sometime in the mid-1600s, though we can't be certain, we found him in the census for Rionegro for the year 1666, and that's as far as we could go on this branch of John's family tree.

However, we weren't done with his mother's ancestry, not by a long shot...

Focusing on another of John's maternal lines, we were able to trace back to his 15th great-grandfather, a man named Sebastián de Belalcázar, whose life is exceedingly well-documented for a man of this era.

LEGUIZAMO: This is my 15th great-grandfather?

GATES: How 'bout that?

LEGUIZAMO: That's incredible.

What, what, what does that take us?

Into the 1400s?

GATES: He died around 1551, in what today is Cartagena.

LEGUIZAMO: Wow.

GATES: Would you please read the translated section?

LEGUIZAMO: "I, Sebastián de Belalcázar Adelantado, Governor", Governor!

"and Captain-General of these provinces and district of Popayán for His Majesty, do grant and certify by this instrument my full power of attorney to you, Francisco de Rodas, in all my litigation, civil or criminal.

I grant this instrument before the Notary in the city of Cali."

GATES: Your 15th great-grandfather was the governor and captain-general of the District of Popayán for the King of Spain.

His boss was the King of Spain.

LEGUIZAMO: Wow.

I can't believe it.

I, you could trace me that far back.

That's incredible.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LEGUIZAMO: My, my family's gonna, uh, use the term bug out.

They're gonna freak out and bug out.

GATES: Neither John, nor his family, was likely prepared for what we discovered next.

Records show that Sebastián served under Francisco Pizzaro, the infamous conquistador who brutally subjugated the Incan empire.

Indeed, we found testimony detailing how Pizzaro sent Sebastián into what is now Ecuador to conquer the Incan city of Quito, and seize any treasure that he could find.

Much to John's chagrin, Sebastián did exactly as he was told...

Your ancestor was able to obtain vast amounts of gold for Spain, your ancestor, not only from the mines of the area, but he and his cohort also melted down what Inca gold was left in the city.

LEGUIZAMO: I mean, it's one of the great crimes of, of history, you know?

I mean the, the incredible artifacts and, and, and the, and museum pieces that were melted.

GATES: Right.

LEGUIZAMO: On one side, we made them, and the other side, we melted them, you know?

I'm, I'm, I'm kind, I'm kind of like Dr. Jekyll and Hyde in here.

GATES: How does it feel to know that you descend, you have blood from, you share DNA with... LEGUIZAMO: I, I... GATES: Both a conquistador line and a noble Indigenous line.

LEGUIZAMO: Yeah.

Yeah.

I mean it's wild.

I mean, you, you hear a lot of, like, great Chicano poets, activists in the '60s going, I, I conquered myself, you know?

We, it's basically that, you know?

Here is my conquistador grandfather and, and, and my Indigenous line, line, you know, and they, they were at, at odds but also, you know, mix, mixing up in the, in the, in the dark.

GATES: There was one more beat to this story.

After the conquest of Quito, Sebastian broke with Pizzaro and went north into what is today Colombia, where, under license from the Spanish crown, he won fame that would endure for centuries.

LEGUIZAMO: No, get outta here.

A statue.

GATES: Yes.

LEGUIZAMO: That's wild.

Wow.

GATES: It's located in the city of Popayán, which he founded... LEGUIZAMO: Oh wow.

GATES: In the year 1537, three years after the conquest of Quito.

And Popayán wasn't the only city he founded.

See that map?

LEGUIZAMO: Yeah.

GATES: Your ancestor founded all of those cities.

LEGUIZAMO: No!

That's amazing.

I mean, those are big cities in Colombia.

GATES: Big cities.

LEGUIZAMO: Yeah.

I mean it's, it's so unfathomable.

GATES: Well, guess what?

A month ago, protesters pulled this statue down.

LEGUIZAMO: Oh, they did?

GATES: Indigenous protesters.

LEGUIZAMO: I had a feeling it had to go.

GATES: A month ago, in September.

LEGUIZAMO: Oh, man.

I hope they put it in a museum.

I mean, maybe it doesn't need to be...

I mean, I'm not against that.

I understand... GATES: Sure.

LEGUIZAMO: The horrors of destroying a people's culture, language, and religion.

And stealing all that they had, and now they're living in, in, in, in squalor.

Yeah, no, I'm not, I'm not for that, you know what I mean?

GATES: Well, I mean, he was a big target, right?

LEGUIZAMO: Yeah.

Yeah.

But I'm glad you got that photo quick.

GATES: Much like John, my second guest, Lena Waithe, was about to follow her roots back centuries to meet ancestors whose stories, and identities, had been lost to time.

But this journey began much closer to home: with Lena's father, Lawrence David Waithe... Lawrence separated from Lena's mother when Lena was a child, and though he remained in her life for several years afterwards, he died young... Leaving his daughter with a host of unanswered questions.

WAITHE: He came around on weekends, you know, for a little while, and then, and that was cool, and it was totally normal, and then it stopped, and I didn't really understand why, and I think there were things that were going on that maybe they didn't think a child should know, so all I knew was the, the weekend visits stopped, and, and then, when I was 15, uh, he died suddenly.

GATES: Yeah.

WAITHE: And I just sort of didn't know, I didn't know what to make of it.

It's just a very odd thing to hear.

Even if you haven't seen a parent in a long time, there's still something that shifts in the universe that a person who helped make you is no longer here.

And I think I was just sort of very lost and didn't know what to make of it, uh, and I think I still don't.

GATES: You carry the Waithe name.

Do you know where it comes from?

WAITHE: I do not.

GATES: Lena's father was born in Boston in 1951.

As we set out to trace his roots, we expected that they would lead us into the American south, as do the roots of most of my African American guests.

And, indeed, Lawrence's mother has ancestry in Tennessee, Alabama and Georgia.

But when we turned to Lawrence's father, we found ourselves in New York City, where, in 1921, a man named Winston Waithe stepped off a ship.

Winston is Lena's great-grandfather.

And, according to the passenger list of his ship, he wasn't coming to New York from Charleston, or New Orleans, or anywhere in the United States.

He, and this whole line of Lena's ancestry, was from Barbados, in the West Indies.

WAITHE: Wow.

Barbados.

GATES: So, you had no idea of any of this?

WAITHE: No.

GATES: Nothing, where they came from or how they came to the, well, obviously, if you didn't know where they came from, you hadn't ever... WAITHE: Yeah.

GATES: Thought about how they got here.

WAITHE: Absolutely.

GATES: What's it like for you to see that?

WAITHE: That's the interesting thing, I never thought of my ancestors as immigrants.

GATES: Oh, right.

WAITHE: Yeah, because, you know, you know, we, you think, well, we didn't want to come here.

You know, there's a difference, you know, being brought over here against your will versus, you know, choosing to come, so I think that's the most shocking thing.

GATES: Yeah, we were unwilling immigrants, right?

WAITHE: Yeah.

GATES: Not you.

WAITHE: Yeah, I know.

So interesting.

GATES: In Winston's day, Barbados was an English colony, and Lena wondered why her ancestor would leave his homeland to take a chance in segregated America.

The answer, it seems, was economic... WAITHE: "The Barbados have become so full of people that the English government offers a cash bonus to any inhabitant who will agree to leave the island and stay away for five years."

"Ordinarily, the offer is $20, but when Barbados people are least inclined to leave their island it is raised to $25."

Wow.

So, they were kind of bribed to go away?

GATES: Yeah.

WAITHE: Wow.

GATES: They had an overcrowding problem, and they go, "Here's 25 bucks, you know, like you all..." WAITHE: "Get out."

GATES: "Get out," right?

WAITHE: "Go somewhere."

Wow.

GATES: The English government was paying people to leave.

And I didn't even know.

I mean, until we did the research of your family tree, I didn't even know that anybody was doing this.

WAITHE: This is crazy.

GATES: Winston was 17 years old when he left Barbados.

But the cash offer wasn't the only incentive drawing him north.

Wages were higher in the United States.

And there may have been another factor as well: Winston wasn't the first in his family to make the move.

As evidenced by the passenger list of the ship that brought him here.

WAITHE: "Whether going to join a relative or friend, father, Mr. E. Waithe, 123 Houston Street Cambridge, Massachusetts."

GATES: So, you know what's going on here?

Your great-grandfather Winston came to the United States on his way to be with his father... WAITHE: Oh.

GATES: Who was already here.

WAITHE: Got it.

GATES: Your great-great grandfather Edward Waithe, who was living in my beloved Cambridge, Massachusetts, not that far from my house.

WAITHE: Wow.

GATES: So, your great-grandfather wasn't the first immigrant on your family tree.

WAITHE: Hmm.

Wow.

GATES: What's it like to learn this information about two generations of your blood ancestors?

WAITHE: I mean, it's, it's really beautiful.

It feels like I have a sense of, a newer sense of identity.

GATES: So, are you going to visit Barbados?

WAITHE: I must, for sure.

I can't wait.

GATES: And you probably have cousins all over there, and I bet they're looking at your film saying... WAITHE: They're like, "You look familiar."

Wow.

GATES: We now set out to see what we could learn about Lena's roots in her newfound ancestral home.

We knew that we faced a steep challenge...

Doing genealogy in the West Indies can be very difficult because many vital records have been lost.

But in Lena's case, we got lucky.

We uncovered a wedding record from the year 1880 that allowed us to add two more generations to her family tree... WAITHE: "The Parish Church of Christ Church.

When married, March 27.

Name and surname, William Moore Waithe, age 38 and Charlotte Ann Warner, age 37.

Father's name and surname, Primus Waithe."

GATES: William Moore Waithe is your third great-grandfather.

He was born almost 200 years ago in 1830 in Christ Church Barbados.

And you just read the name of his father, Primus Waithe.

WAITHE: Wow.

GATES: Primus Waithe is your great-great-great- great-grandfather.

WAITHE: Wow.

GATES: He was born around 1792 also in Barbados.

Remember when George Washington was president of the United States?

WAITHE: Oh, man, it's amazing.

Yes.

GATES: Your fourth great-grandfather.

WAITHE: I love that name, Primus.

GATES: Primus, it's cool.

WAITHE: That's a strong name.

GATES: This record not only lists the names of Lena's direct ancestors, it places them in a specific parish in Barbados, a parish known as Christ Church... And this would tie Lena to a terrible chapter in Barbados' history.

As we pored over the archives of Christ Church, we discovered a slave register from the year 1817, indicating that Lena's fourth great-grandfather Primus was the human property of someone with a very familiar name...

He was enslaved by a woman named Mary Murrell Waithe.

WAITHE: Whoa.

GATES: And that is where you get your surname from.

WAITHE: Wow.

GATES: The Waithe family.

WAITHE: It was always such an odd last name, like, growing up.

GATES: Mhm.

WAITHE: It wasn't like the other, like other Black kids I was around, like, like Washington or Johnson, and things like that, it was always a, people always struggled with spelling it, pronouncing it.

Like, I was just always trying to tell people understand it, but I, yeah, wow.

GATES: What's it like finally to know?

WAITHE: You know, it's all, it's, it's painful because your name is such a huge part of your identity, so for someone to put their identity onto your family, it just feels, uh, unjust.

GATES: Lena's family wasn't alone: over the course of the transatlantic slave trade, roughly 600,000 Africans were shipped to Barbados.

More than came to the entire United States.

Most ended up on sugar plantations, where conditions were utterly hellish... Scholars told us that Primus likely worked six days a week, doing 12 hour shifts of the hardest labor, clearing land, digging holes, and cutting the sugar cane, all the while dealing with oppressive heat and poor sanitation.

It was both terrifying, and deadly, as massive numbers died of exhaustion, starvation, and disease.

Indeed: the average life expectancy of an enslaved male worker on a sugar plantation was between seven and nine years... Before the opening of the West Indies and the growing cultivation of sugar there... WAITHE: Uh-hum.

GATES: Only rich people in Europe could have sugar.

WAITHE: Oh, wow.

GATES: The West Indies made sugar the world's first commodity crop.

WAITHE: Wow.

GATES: And sugar was gold.

People made vast fortunes, but to harvest that sugar, they needed free, cheap labor.

And that labor, of course, came from Africa.

WAITHE: Yeah.

GATES: What's it like to hear those numbers?

WAITHE: Just to think about their lives and them not being able to explore themselves or step into themselves or have the time to get to know themselves because they were just being worked to death, literally.

GATES: Mmm.

WAITHE: It's, it's devastating, and it's so disturbing.

It doesn't matter how much of it you read, you're still, I think there's just a level of, uh, just of not being able to understand that will, I don't think it will ever come.

It's not meant to be understood.

GATES: Slavery dominated Barbados for more than two centuries, but the Africans who were caught up in this ruthless system didn't succumb in silence.

There were many acts of resistance, both small and large... And, in the spring of 1816, one of them shook the world.

WAITHE: "On Easter Sunday, April 14, an insurrection of the slaves at Barbados broke out.

An account received on Monday states that 41 estates were actually destroyed, and that the insurrection appeared to be very extensive, and the slaves most ferocious.

The Negroes first proceeded to demolish the overseers' houses.

They then destroyed the sugar-pans and all the implements, which they could gain possession of, also all the Negro huts."

Wow.

Wow.

Well, be still my heart.

Wow.

Well, I love that.

GATES: The "insurrection," as newspapers called it, came to be known as Bussa's Rebellion, the biggest slave revolt in the history of Barbados.

It lasted three days before it was put down by the British army, leaving dozens of plantations destroyed and miles of sugar fields burned.

Lena's fourth great-grandfather was 24 years old at the time.

He likely knew about the plans, and he most certainly saw smoke from the burning fields, but we don't believe that he played an active role in the revolt, for one very simple reason, he survived.

Although Christ Church was one of the parishes impacted by the rebellion, all people who were known to have participated were executed, but Primus wasn't, Primus lived to father your third great-grandfather William in 1830.

WAITHE: Wow.

GATES: If Primus had been involved, we would just erase you right now and you would just disappear.

WAITHE: Wow.

Wow.

Whew.

Wow.

GATES: What do you make of all this?

WAITHE: Oh, it's so interesting because I wonder if he wanted to be involved but was too afraid or, wow.

I'm sure there was some survivor's remorse, uhm, but I'm grateful he did.

GATES: I'm grateful he did, too.

Lena, unfortunately, Primus would never know freedom.

WAITHE: Oh.

GATES: He would never ever be released from bondage.

He died enslaved in Barbados sometime between 1829 and 1832, and slavery is not abolished throughout the British Empire until 1834, so just before the Abolition of Slavery.

WAITHE: It would've been beautiful if he could've seen that, but I'm happy, but I'm happy he saw the fires instead.

GATES: Yep.

We had a final detail to share.

The same archives in Christ Church that held a record of Primus' enslavement also held another record, of a far more optimistic nature... WAITHE: "When born, 1867, August 8.

Child's Christian name, Edward Albert.

Surname, Waithe."

GATES: Any idea what you're looking at?

WAITHE: I don't.

GATES: That's the baptismal record for your great-great-grandfather... WAITHE: Oh, wow.

GATES: Edward Waithe.

Edward Waithe was Primus's grandson.

WAITHE: Wow.

GATES: And he wasn't only the first immigrant ancestor on your Waithe line, remember he comes to Boston in 1905?

WAITHE: Uh-hum.

GATES: He was also the first person on your family tree, on the Waithe line, to be born free.

WAITHE: Wow.

Wow.

1867.

GATES: Does it change the way you think of your father's family and your relationship to it?

I mean, are you more of a Waithe now?

WAITHE: I'm happy I know where the name comes from.

Um, I think I'm mostly filled with gratitude for all these amazing human beings who, you know, lived and worked and raised their children, and uh, fought, and survived.

GATES: The key word, survived.

WAITHE: Yeah.

By the skin of their teeth.

GATES: We'd already traced John Leguizamo's mother's family back to the early 1500s, revealing his ancient roots in his native Colombia.

Now, turning to his paternal ancestry, we found ourselves facing a mystery.

Growing up, John knew his father's mother, María Emilia Leguizamo, but never met his father's father, his own grandfather, he didn't even know his name.

We were starting, essentially, from scratch... Have you ever heard much about your grandfather?

LEGUIZAMO: I, I mean the only thing I heard was that he was a chicken farmer, and he had a lot of kids.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

What do you know about his relationship to your grandmother?

LEGUIZAMO: To my grandma?

Well, I, I think, I don't know.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LEGUIZAMO: I, I don't, I have no, no stories of him.

I, I don't really have, nothing was passed down to me about him.

I think my father and him were estranged, and uh, so, I, I, I, I, I knew, I knew nothing.

GATES: Lacking first-hand knowledge, John told me that he had long ago made an assumption: he believed his grandfather was Puerto Rican, based on the fact that there's a barrio called "Leguizamo" in one of Puerto Rico's largest cities.

But we could find no evidence of John's family on the island, and his DNA does not show any trace of Puerto Rican heritage.

Instead, John's father's roots lie in the same place as his mother's: Colombia.... And the solution to the mystery lay in the nexus between his grandfather's name, and his unusual life... LEGUIZAMO: "Name of deceased, Martin Vargas-Cualla, place of death, Houston, Texas, date of death, July 29, 1975.

Occupation, self-employed merchant, Birthplace, Bogotá, Colombia, citizen of what country, Colombia."

GATES: Have you ever seen that before?

LEGUIZAMO: No.

Who is that?

GATES: John, this is the death certificate of your grandfather.

LEGUIZAMO: Oh wow.

GATES: He died in Houston, Texas, on July 29, 1975.

He was 80 years old.

LEGUIZAMO: Now, now, why don't I have, I'm not, he's not Legui, Leguizamo.

GATES: Right.

LEGUIZAMO: He's Vargas.

I'm not Vargas.

I'm Leguizamo.

GATES: Your grandmother was not married to Martin.

LEGUIZAMO: Oh, there you go.

GATES: Okay?

She was one of several women with whom he had children and who lived at his properties.

LEGUIZAMO: Oh, wow, my, my grandmother lived in his, one of his properties?

GATES: Yes.

LEGUIZAMO: Oh, okay.

GATES: Yeah.

LEGUIZAMO: So, we didn't take my grandfather's name 'cause that, otherwise I'd be a Vargas.

GATES: You got it.

LEGUIZAMO: Uh-huh.

GATES: But she was there.

She was living... she had children on his property, but... LEGUIZAMO: He didn't claim them.

He didn't claim, he didn't, he didn't claim my father.

GATES: Yeah.

Right.

LEGUIZAMO: Yeah.

That's where all the confusion comes... GATES: There you go.

You got it.

LEGUIZAMO: So, I should be a Vargas.

I should be John Alberto Vargas.

Johnny Vargas.

GATES: Johnny Vargas.

LEGUIZAMO: Johnny Vargas.

GATES: This record indicates that John's grandfather was a "merchant."

John had heard he was also a chicken farmer.

Both were true, in part.

It seems that Martin was actually successful in many realms, and made a substantial fortune as a rancher and a businessman.

This made him a prominent figure in Colombia.

Indeed, we found newspaper articles dating back to the 1950s detailing his very colorful career... LEGUIZAMO: "Don Martin Vargas Cualla is a character out of a novel.

A familial or academic setback threw him into the capital city when he was beginning his adolescence.

For ten pesos, he bought two old horses that he later sold at 25, and that was the beginning.

Animals and lands allowed him to multiply in a world that was his own, estate after estate, beasts, and cattle.

The previous owner of those old horses is a breeder of beautiful specimens and a creator of riches."

GATES: Any word of this... LEGUIZAMO: No, no.

GATES: Never passed down in your family?

LEGUIZAMO: No.

Nobody... GATES: Why?

LEGUIZAMO: I, I don't, I don't know what was going on in my family.

I mean, uh, was it, were, were the people just not proud or, or, or, or because they were, or because he was a natural instead of a legitimate son?

GATES: Mhm.

LEGUIZAMO: I think, a lot of my father's own, demons, kind of... GATES: Yeah.

LEGUIZAMO: Haunting him his whole life.

'Cause he was always, my father was always, never satisfied with what, what he did, never, always constantly questing for more, always trying to be better, always trying to... GATES: Hey, I come from people, I had a fortune, I want to get it back.

LEGUIZAMO: Yeah.

Yeah.

GATES: Somehow disappeared.

LEGUIZAMO: 'Cause he never got it.

He never got it 'cause he wasn't legitimate to, to the will.

GATES: Right, you got it.

LEGUIZAMO: Wow.

That's crazy.

GATES: It turns out that Martin wasn't the only prominent figure on this branch of John's tree.

Moving back two generations, we came to a man named Higinio Cualla.

Higinio is John's great-great-grandfather, and his obituary, published in Colombia in 1927, is a litany of impressive accomplishments.

LEGUIZAMO: "Yesterday passed away Don Higinio Cualla, at the age of 87 years.

Bogotá will always remember with gratitude the best of our mayors.

His love for the city, his commitment to the common good, the enthusiasm with which he worked on all hours for the progress of the capital can never be forgotten.

He was the real initiator of the development of modern Bogotá.

Many of the improvements that we enjoy today are owed to him.

It is a shame that his grand spirit did not continue to inspire his successors."

GATES: Pretty amazing, isn't it?

LEGUIZAMO: As a mayor of Bogotá?

GATES: For 16 years.

LEGUIZAMO: Wow.

GATES: From 1884 to 1900.

LEGUIZAMO: That's wild.

I, we, but we never, nobody ever acknowledged that.

Nobody ever passed that down to me, telling me that, you know, I'm the son of, I'm, I'm the great-grandson of a mayor.

GATES: Yeah!

How do you feel about that?

LEGUIZAMO: I, I, my chest is pumped up a little bit.

I do feel a little, uh, boastful, and I'm gonna have to try to calm myself.

GATES: This obituary claims that Higinio helped modernize Bogotá, and the historical record bears that out.

After taking office in 1884, the Cualla administration helped bring electricity to the city, built trolley lines, a theater, and an aqueduct, all the while fixing roads and establishing a tax to help the city's poor.

LEGUIZAMO: Wow.

GATES: He truly was industrious.

LEGUIZAMO: And he was compassionate: "Shelter for beggars".

GATES: And on the left, there's a monument.

LEGUIZAMO: Oh, did they knock that one down, too?

GATES: It's another monument, a monument... Now, the good news, it's still standing.

LEGUIZAMO: Oh, it is?

Yeah, he, he didn't do anything dastardly.

GATES: And you've never seen that before?

LEGUIZAMO: No, I mean who would've thunk?

GATES: But look at this.

Your 15th great-grandfather Sebastián was a statue.

LEGUIZAMO: Yeah.

Yeah.

GATES: Your great-great- grandfather, a statue.

That's amazing.

LEGUIZAMO: Yeah.

Yeah.

GATES: How do you think these stories got lost?

I mean you have two sets of stories that got lost.

LEGUIZAMO: Yeah.

Yeah.

Yeah, all, all of it.

I mean I, I, I think that's a lot, uh, really true for a lot of Latin people, and you know, uh, the conquest was a brutal thing where people were, you know, you were destroying a culture, you're mixing with it, you're, they're, they're sexually attracted, so you're creating a, a new culture, but it, but, but at that same time, things are being hidden.

There's a lot of shaming.

There's a lot of hiding and, and I don't know.

I think it, that doesn't totally disappear that easily over a couple of centuries, and I think that's part of it.

There's a lot of stuff that's hidden, and I think there's a lot of shame in, in, in the conquest, and, and that continues and perpetuates, sort of like a PTSD.

GATES: Turning to DNA, we can see how this complex history is reflected in John's own chromosomes... His admixture indicates that he's a blend of Native American, European and sub-Saharan African... And when we looked at his mitochondrial DNA, the genetic fingerprint that's passed down from mother-to-child across generations, we were able to pinpoint the geographic origins of his direct maternal ancestors.

You want to guess?

Was she European, was she African, or was she Indigenous?

LEGUIZAMO: I would say Indigenous.

GATES: Okay.

But why?

LEGUIZAMO: Because the conquistadors were, were mostly male.

GATES: Uh-huh.

LEGUIZAMO: And, and, and the women that they had affairs with were mostly Indigenous or African.

Yeah.

Yeah.

GATES: Please turn the page.

Very good guess.

LEGUIZAMO: Aha.

Tsssssss... GATES: Your maternal haplogroup or, or clan is called B2d.

The map there shows your where your direct maternal ancestors came from.

As you can see, they all came from the Americas.

LEGUIZAMO: Yeah, Indigenous, yeah, yeah.

GATES: How does it make you feel?

LEGUIZAMO: I mean, uh, it's beautiful to know about my, you know, that I'm related to the Aztecs and the Mayas and the Incas.

Uh, uh, I take great pride in that.

GATES: Yeah.

LEGUIZAMO: And to know that I, I, I am a quarter of that and... is, is amazing.

GATES: While John was delighted by his DNA results, they were not a complete surprise.

But that wasn't the case with Lena Waithe.

When we examined her mitochondrial DNA, believing it would take us back to Africa, we found ourselves somewhere completely unexpected... You descend from a Native American woman.

WAITHE: What?

GATES: One of your umpteenth great-great-grandmothers was a Native American.

WAITHE: Wow.

GATES: Isn't that cool?

WAITHE: That's a huge surprise.

I, I, uhm, wow.

I, I wasn't expecting that.

GATES: Neither was I. Lena's mitochondrial DNA ties her to a subgroup of what's known as "haplogroup B", one of four major Native American haplogroups.

This means that Lena's direct maternal ancestors crossed into North America more than 15,000 years ago.

Causing Lena to re-imagine, once again, her family's story... You're descended from willing immigrants, and unwilling immigrants.

WAITHE: Unwilling immigrants.

GATES: Right.

WAITHE: Yeah, I thought it was all unwilling, so yeah.

GATES: And, and on one line, your mother's, mother's line, somebody was sitting here watching when all these people showed up.

WAITHE: Yeah, absolutely.

GATES: Black, white, and, and in-between.

WAITHE: And, and I'm sure she wasn't happy about it, but you know... All right, I'm gonna walk taller now.

I am, now that I know.

GATES: The paper trail had run out for each of my guests.

It was time to unfurl their full family trees... WAITHE: Wow.

GATES: Now filled with names they'd never heard before.

LEGUIZAMO: That's a lot of people.

GATES: Giving each the chance to reflect on the incredible journeys that had produced their families, and their identities... LEGUIZAMO: You know, you feel empowered in some way.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LEGUIZAMO: You feel like you have this, all these people behind you, all these ancestors, you know?

You just don't, you don't feel like you're just some spontaneous generation, you know?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LEGUIZAMO: That's beautiful.

Thank you.

GATES: Does anything that we've shared change anything about the way you see yourself?

WAITHE: I think it has.

I, even though I knew I have a, a last name that can kind of give you, me a hint that I come from, you know, an island or Caribbean, but I think I've always just thought of myself as, and my ancestors as American.

GATES: Right.

WAITHE: As... you know... and thinking of, knowing that my ancestors are immigrants, and, and chose to come to this country, just gives me a whole new perspective.

GATES: You're from elsewhere.

WAITHE: Yes.

Yeah.

Yeah.

I'll take it.

GATES: That's the end of our journey with Lena Waithe and John Leguizamo.

Join me next time when we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests, on another episode of Finding Your Roots.

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S8 Ep7 | 32s | Henry Louis Gates, Jr. helps John Leguizamo and Lena Waithe retrace their ancestral paths. (32s)

John Leguizamo Learns About His 9th Great-Grandfather

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep7 | 1m 6s | John Leguizamo is stunned by how far back his lineage has been traced. (1m 6s)

John Leguizamo’s Lineage is Traced Back 17 Generations

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep7 | 1m | We traced John Leguizamo’s lineage back to 17 generations of surprising ancestors. (1m)

Lena Waithe Discovers Her First Free, Post-Slavery Ancestor

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep7 | 1m 36s | Lena Waithe expresses gratitude for the unimaginable hardships her ancestors endured. (1m 36s)

Lena Waithe Learns Grim Statistics on Slave Life Expectancy

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep7 | 1m 22s | Lena Waithe learns about the short life expectancy of slaves on a sugar plantation. (1m 22s)

Lena Waithe Learns the Source of the Name “Waithe”

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep7 | 1m 21s | Lena Waithe reacts to hearing that her surname derives from slave owners in Barbados. (1m 21s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- History

Great Migrations: A People on The Move

Great Migrations explores how a series of Black migrations have shaped America.

Support for PBS provided by: